The merits of moving money offshore

This article was first published in the Quarter 4 2020 edition of Consider this. Click here to download the complete edition.

Key take-aways

- In the current grim prevailing investment narrative, South African assets are doomed to underperform their offshore counterparts and the economy is set to remain weak; therefore investors need to have a large amount of their funds offshore.

- However, the facts show that historically the JSE has outperformed global equities over long periods. It is their more recent underperformance that is dominating the current narrative.

- Currently SA equities and bonds represent excellent value compared to developed country markets, offering strong prospective returns. While SA bonds do carry higher risks than in the past, Prudential does not believe that government default is likely in the near term. History shows that when valuations are significantly in favour of South African assets, as they are currently, subsequent long-term returns eventually reflect this.

There is currently a narrative among some investors that holding local assets has been a disaster for South African investors, even over multi-decade periods, and that now is the time to save whatever crumbs are left and move everything into the safety of hard-currency assets. Following are some observations on this view (from an investment returns perspective) which may give investors pause for thought.

A grim view

How can this have happened? Investment theory suggests higher-risk emerging markets should deliver a risk premium over their developed peers in the longer term, albeit with a bumpier ride. But South Africa has failed to reach its growth potential, they say. While Asian markets roared ahead after the late ‘90s crisis, South Africa struggled to break a sweat, bar a few brief years in the mid-noughties when a commodity and credit bubble delivered a decent 5% real return only to find that it had all been borrowed from the future. The cracks emerged post the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), and over the ensuing decade they widened to chasms into which investment and consumption plans were quietly discarded and what was left staggered forward, weighed down by the millstone of widespread corruption and graft. What hope is there then for the future? The final chapter of this narrative does not see South Africa benefitting from economic absolution, a wiping clean of the slate and a period of long-awaited renewal. South African assets are doomed to underperform, companies to struggle to generate decent earnings growth, and bonds to face the inevitable march into the jaws of default.

The question is, though, is this story fact or fiction? And either way, is the outlook as pre-determined as this bleak narrative suggests? We need to be circumspect about relying on our emotions when it comes to investment decisions; human beings are poor judges of facts because our emotions colour our interpretations and recollections of the past. Recent poor experiences can receive disproportionate attention that blurs prior history. Our feeling is that things are really bad now, they must always have been like this and are therefore likely to continue forever into the future. There is no doubt South African investors have had a grim time of it more recently, but is this a full and fair exposition of history?

A great long-term investment in the past

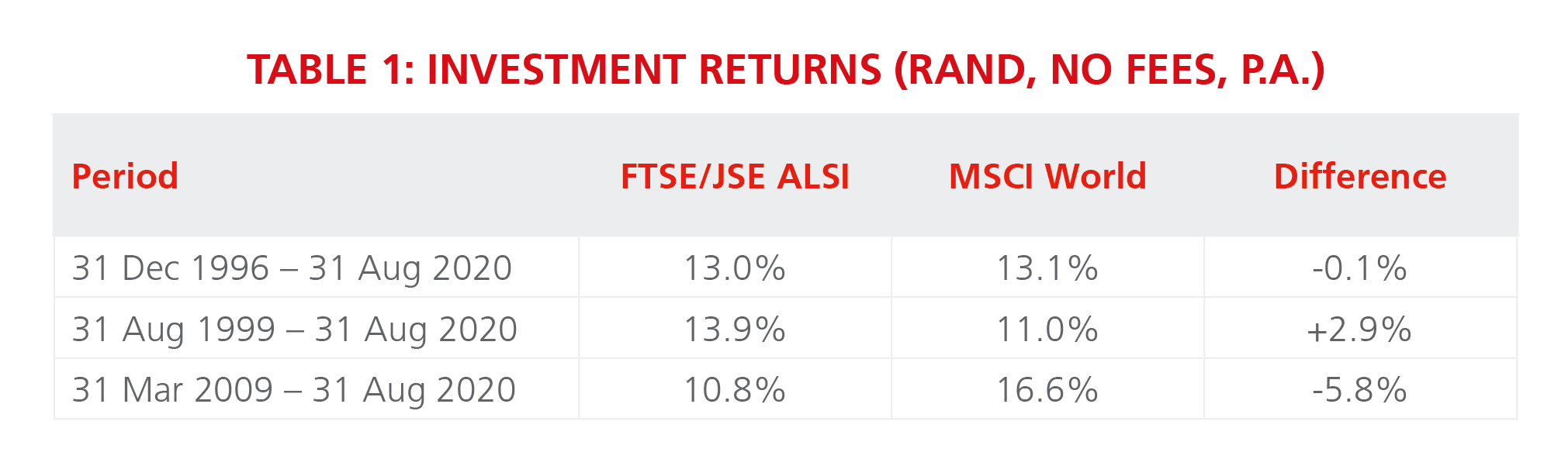

Table 1 details the long-term investment returns of the FTSE/JSE All Share Index (ALSI) against the MSCI World Index (an index of developed market equities). From the end of 1996 until end-August 2020, the ALSI has matched the MSCI World almost exactly in rand terms. That hardly seems like a disaster, and end ’96 is a fairly punitive starting point as South Africa was just about to be battered by the fallout from the 1997 Asian Crisis and the 1998 Russian default. If you roll the starting point forward to August 1999, giving 20 years of history, the ALSI has beaten the MSCI World in rand terms by 2.9% per annum over two decades, which includes the recent poor performance of the SA equity market. An initial R100 investment has become R1,570 if left to work in the South Africa equity market; the same R100 in offshore equities only R920. That is an extraordinary difference. This makes it hard to reconcile the prevailing sense of despair which accompanies holding SA assets with the fact that they have been a great long-term investment, just as theory suggests.

11 years of relative underperformance

Table 1 also shows why it is we feel so despondent. Since end-March 2009, the low point for global equities during the GFC, the MSCI World has outperformed the ALSI by 5.8% p.a. The value of R100 invested offshore during this period would have generated R630, more than double what leaving your money in South African equities has delivered. The truth then, is that it is not the long term which has been the problem, it is the past 11 years which has been a relative disaster.

In absolute terms, since the GFC South African investors have still almost tripled their money locally, but compared to offshore it feels like we’ve become the poor cousin. It is natural to extrapolate recent experience both forward and backward in time, following the mantra “It has always been like this and it always will be”. That the facts show that South Africa has in the past offered exemplary returns should give pause for thought at the very least. Could it do so again?

SA valuations relatively cheap

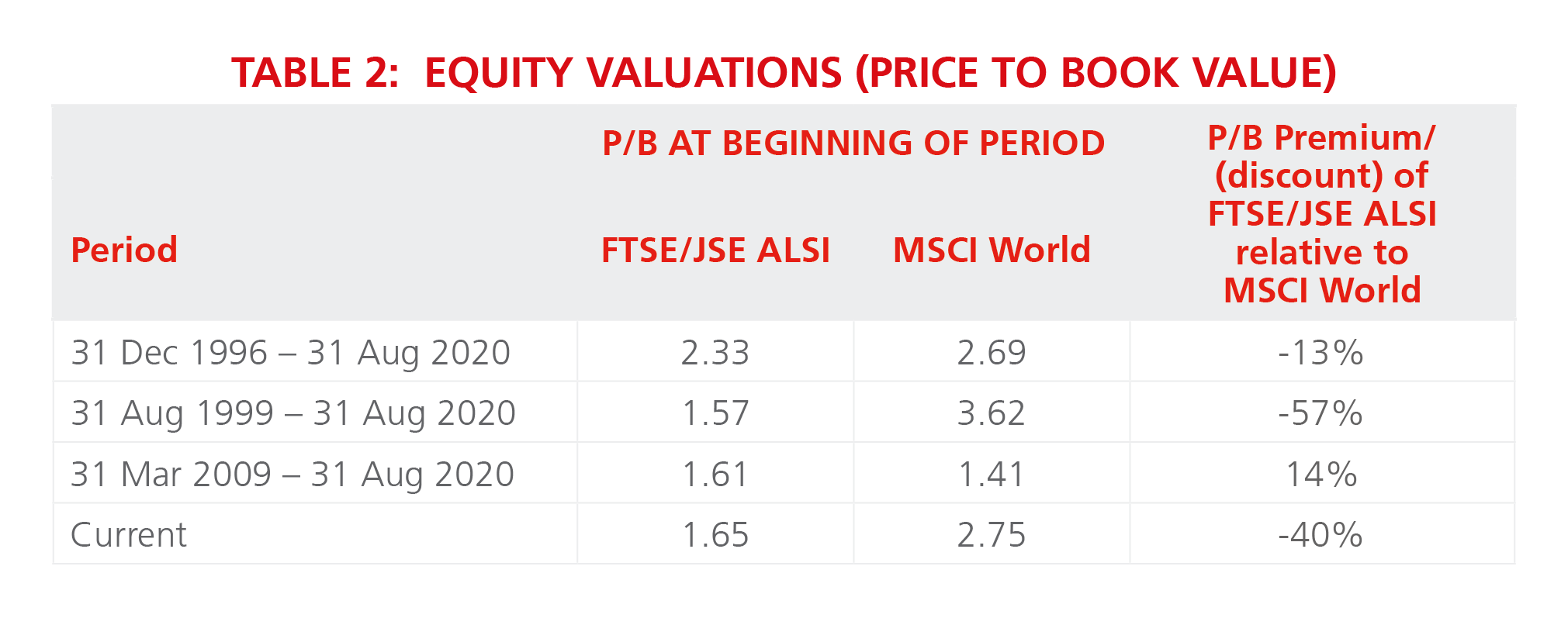

Prudential approaches this question by asking what current market valuations can tell us about future prospective returns. Taking the same periods as in Table 1, Table 2 shows a common equity market valuation indicator, the Price to Book value ratio (P/B), at the start of each period.

If we correlate these valuations to the returns in Table 1, the data suggests that when the ALSI has traded at a very substantial discount to the MSCI World, subsequent long-term returns have tended to be very good. At the end of 1996, the two markets were trading on similar P/B levels and then delivered similar returns, but in late 1999, almost three years later, the ALSI had de-rated significantly to 1.57 while developed world equity markets had re-rated to a sky-high 3.62 P/B. Given this, perhaps it is not surprising that the subsequent returns over two decades massively favoured South Africa.

Today we find ourselves in a similar situation: current valuations are significantly in favour of South Africa. With a P/B of 1.65, the ALSI is offering a 40% discount compared to that of the MSCI World at 2.75. Although this isn’t as extreme as late 1999, it suggests analysts already expect a far more favourable environment for developed markets, whereas a good deal of pessimism sits in South African valuations. The distribution of potential outcomes from this starting point favours South Africa.

Forecasting the future

Of course this is not a guarantee that local equities will outperform developed markets going forward, or even that returns will be high versus their history on an absolute basis. However, it certainly challenges the notion that there is nothing on offer for investors in South Africa equities. Investors can seek to justify the current ALSI valuation on the basis of poor fundamentals, a hollowing out of our industrial capacity, of institutionalised graft, of policy paralysis that prevents much needed economic transformation and reform. Remember, however, that it is more-or-less impossible to buy an asset with a good story at a cheap price, and recognise that the narrative now has to change from “SA equities have always been rubbish” to one where it is understood that they have done well long-term but now one has formed a view that this history isn’t going to repeat. Then ask: “How hard do I want to back my view of the future relative to anyone else’s; why do I think I am better at forecasting the future than the market?” Placing all your eggs into the hard currency basket, against what the valuations suggest and on the back of a view, is a big call.

What about SA bonds?

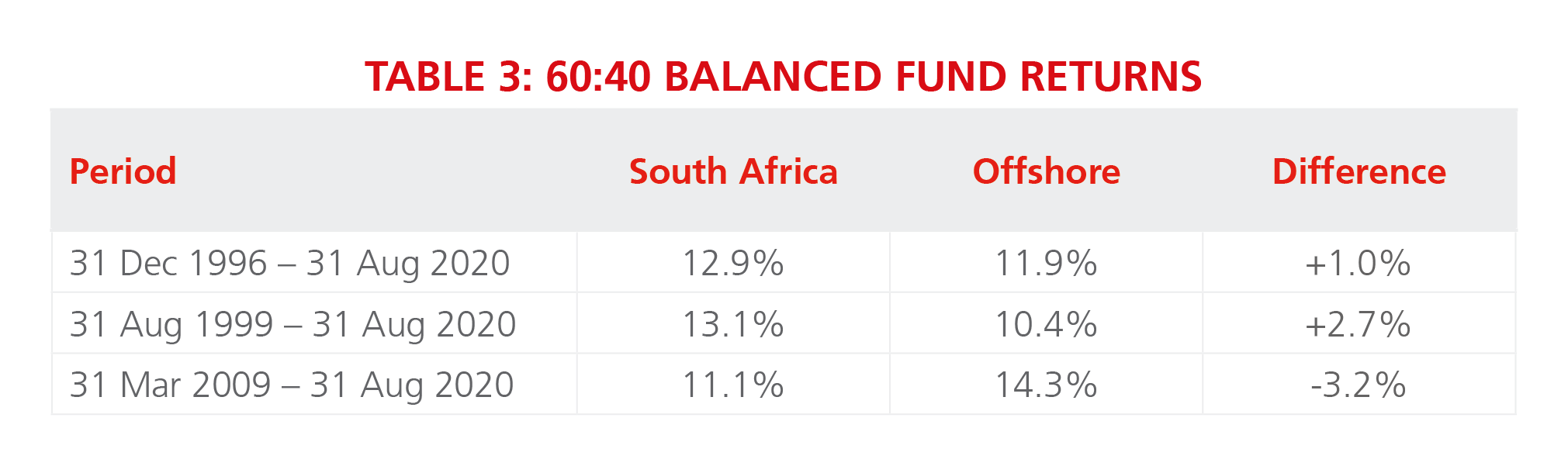

But clients don’t just own equities. Most investors own balanced funds, multi-asset products. A separate line of attack might suggest that while SA equities have done well over the long term, SA bonds can’t have been a great investment. Look at current yields, with 20-year government bonds at over 11% when their US equivalents are barely over 1%. Table 3 shows returns for a 60:40 equities:bonds balanced fund in South Africa and offshore. The SA portfolio uses the FTSE/JSE All Share and All Bond Indices, while offshore we look at the MSCI World and World Government Bond Indices.

Even when we incorporate bonds into a portfolio, the history is much the same. Investors in a domestic South African balanced fund have done well over the past two decades, despite the precipitous fall in global bond yields. However, as with equities, the post-GFC period has been relatively poor for South African bonds, and we would suggest that this leaves investors determined to avoid repeating this past decade in the decade to come -- irrespective of the attractive valuation signal at hand.

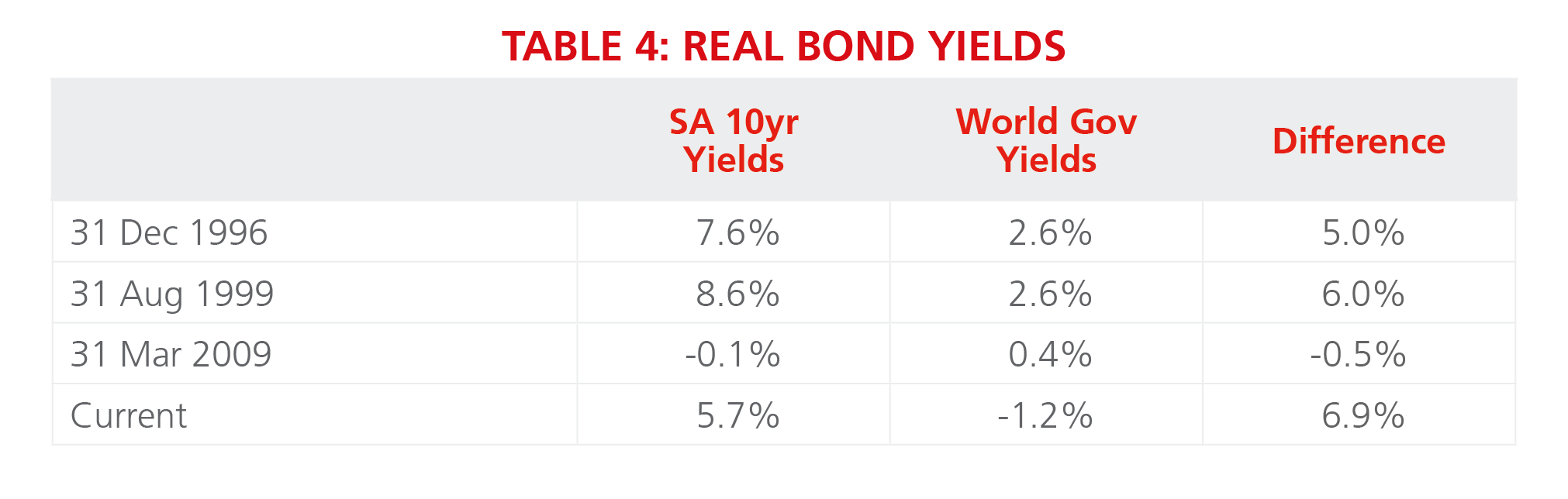

We have seen that SA equity valuations appear to favour the performance of the local market against its developed peers going forward, but is this also true for SA bonds? The classic indicator is the inflation-adjusted yield. We have used the average inflation rate over the previous three years as a proxy for market expectations at each valuation point.

Is near-term government default likely?

As Table 4 highlights, the current difference between South African real 10-year government bond real yields and their global peers is a substantial 6.9% – higher than it was in either 1996 or 1999 – and very attractive by comparison. High nominal yields in SA combined with falling inflation have increased real yields on offer. In global markets, while inflation is very low it remains in positive territory and nominal yields are close to zero, leading to negative real yields. From this starting point only a view of a near-term default by South Africa would undermine the valuation advantage. This is not impossible, but the absence of significant quantities of foreign-denominated debt leaves South Africa as a non-traditional candidate for default. SA also has well-developed domestic financial markets unlike most emerging markets, with a substantial private sector savings industry, creating potential ‘self-help’ levers that are available to postpone default for a considerable period and/or avoid it altogether, even if National Treasury doesn’t manage to achieve its full fiscal consolidation objectives.

Rand weakness favours local investing

A final factor to consider in the “offshore or bust” argument is the current valuation of the rand. Since the start of the Coronavirus crisis in March, the rand, along with its emerging market peers, has depreciated significantly against the major global currencies as investor sentiment turned extremely risk averse and as local conditions deteriorated. Since then, notwithstanding more recent US dollar weakness, it has remained undervalued as measured by its purchasing power parity compared to history. This would suggest the rand would be likely to appreciate against the major global currencies from current levels, thereby eroding offshore returns in rand terms. Equally, buying offshore assets now with undervalued rands is like waiting until prices rise to buy the latest smartphone.

In conclusion, history suggests that when valuations are significantly in favour of South African assets, subsequent long-term returns eventually reflect this. This is generally true for assets globally, not just in our own case. It is certainly erroneous to think that investing in domestic bond and equity markets has always been a losing strategy. The implementation of a view premised on this thought ignores prevailing valuations which across asset classes suggest there is a high probability that favouring offshore markets at this point will eventually prove to be a value-destroying trade.

In light of the above considerations, but especially the current valuation signals, Prudential’s house view portfolios are underweight offshore equities and bonds compared to our peers. We are instead overweight high-quality, well-valued SA stocks and long-dated government bond that we expect will deliver superior returns over the next five years.

For more information, please contact your Financial Adviser, our Client Services Team on 0860 105 775 or email us at query@prudential.co.za.

Share

Did you enjoy this article?

South Africa

South Africa Namibia

Namibia

Get the Newsletter

Get the Newsletter