Investment risk through the Covid-19 crash

This article was first published in the Quarter 4 2022 edition of Consider this. Click here to download the complete edition.

Key Take-Aways:

- In contrast to a much-expected market recovery in early 2020, the Covid-related market crash caused the most severe disruptions to the SA equity and bond markets since the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Global investment managers were caught by surprise.

- We increased the frequency of monitoring of our portfolio risk (tracking error). Our analysis showed it was market volatility, rather than our active positions, that was the primary source of the few brief breaches in our portfolio risk limits. We therefore did not need to reduce any positions to lower portfolio risk, avoiding selling in a down market.

- We were also able to buy up companies at excellent valuations, which provided the base for our portfolio outperformance in subsequent years.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused massive disruption to the world’s economies, while leaving a trail of human destruction in its wake. It provided one of the clearest illustrations we’ve ever had of the notion that, although they are related, “the market is not the economy”. Economic indicators took many months to return to pre-2020 levels, with the evidence of the pandemic etched on time-series charts forever more, but the stock market crash in response to the Covid pandemic was relatively short and sharp, with a drawn-out recovery. Here we take a look back at the worst period of the financial crash, how our markets reacted, and how we as investment managers handled the increased risk it brought to our portfolios. In retrospect, we can see that our processes worked well through an extremely difficult period in the market, while keeping our clients appropriately positioned to benefit from the recovery that followed.

Three things drive active investment risk: market volatility, correlations between assets in the market, and the active exposures held in a portfolio. As active managers, we have control of only one of those to help manage investment risk for our clients: our exposures. So, what happened in the first half of 2020, and what were we exposed to?

Positioned for a 2020 upturn

Let’s start with the portfolio positioning. Apart from a few concerned virologists, the world entered 2020 blissfully unaware of the economic and social disruption that was to unfold. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook report for January 2020 spoke of modest increases to global growth for the year, accompanied by improving market sentiment, with concerns about geopolitical tensions, the trade war between the US and China, and weather-related disasters. Our portfolio positioning and thinking in early 2020 reflected the moderately bullish global sentiment, with cautious optimism on SA equities and bonds.

Given this backdrop, M&G Investments’ portfolios were therefore broadly positioned for an upturn. Our multi-asset funds were long risk assets: they were overweight foreign equities and SA nominal bonds, and depending on the mandate type, some were slightly overweight SA equities as well. Owing to the negative yields on offer in the UK, EU and Japan, we were underweight global sovereign bonds (historically providing a cushion during market crises) but holding some investment grade US and EU corporate bonds.

Our general equity portfolios were overweight SA Banks, Personal Goods (Richemont), Tobacco, Media, General Financials and Chemicals. Crucially (both in a positive and negative sense), we were underweight food and drug retailers, health care and life insurance.

Our equity style positioning was heavily tilted towards stocks we judged to be offering attractive valuations (this is usual, given our investment approach), as well as high beta stocks (or those whose performance amplifies that of the market. The portfolios were tilted away from low volatility and low beta stocks, and without much of the protection that a high-quality tilt would provide during a market crisis.

For both SA nominal and inflation-linked bonds (IBs), our funds were long duration relative to their benchmarks, with overweight positions in bonds with maturities longer than twelve years.

Then came the crash.

Riding out the crash

While we felt somewhat isolated in South Africa from what the Northern hemisphere was grappling with in late January and early February, an increasingly clear picture was emerging: the Chinese government was having to engage herculean measures to stem the spread of the virus, while infected travellers were fanning out across Europe and the Americas. As February progressed, it became apparent that northern Italy had a serious problem, and outbreaks in Iran and South Korea were also progressing apace. On 24 February, the markets finally decided that the impact of an epidemic that extended beyond Asia to the whole world, would be devastating. Over the month that followed, governments across the world issued stay-at-home orders, including South Africa, which shut down on 27 March.

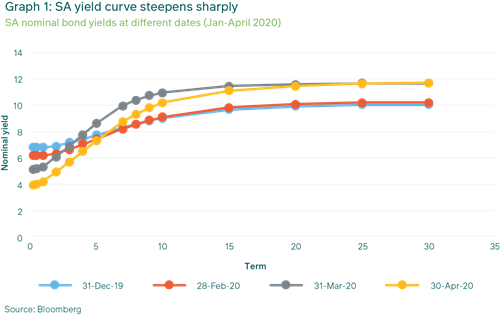

From a South African investment perspective, the Covid crash presented some of the worst short-term equity returns (over all horizons less than one month) that we’ve ever seen. This was also the case for nominal and inflation-linked bonds. Graph 1 shows how the nominal bond yield curve steepened sharply between January and April, with a fall in short-term interest rates and a rise in longer-term rates – real 10-year yields peaked at over 6% (compared to their historic average of around 3%). Plus, bond yields took longer to normalise than equity performance, and we noted increased market volatility and lower new bond issuance for the rest of 2020 and well into 2021.

Although we are still even now experiencing the economic impacts of Covid in many parts of the world, global financial markets began to recover just a month after the initial crash, when it became clear that the Federal Reserve and other central banks would do “whatever it takes” to limit job losses and promote a recovery.

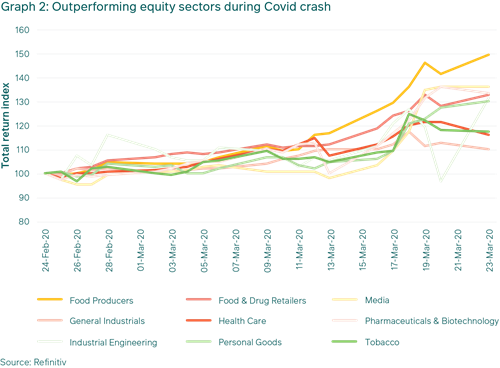

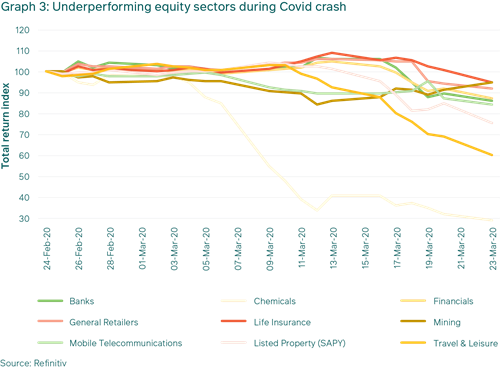

The South African equity market, which had fallen 37% (FTSE/JSE Capped SWIX Index) from its 1 January 2020 value, also began to recover. The recovery was slow and uneven, however, and it was only towards the end of 2020 that the market returned to the levels it had attained at the end of 2019. Graphs 2 and 3 highlight the outperforming and underperforming sectors over the February-March period. Note that our portfolios were overweight sectors shown in shades of green, and underweight those coloured orange-yellow-red.

The graphs show SA equity sectors’ performance during the worst of the crisis. Defensive sectors less impacted by the shutdown fared the best, like Food Producers, Food and Drug Retailers, Tobacco and Health Care. The worst-performing sectors included Chemicals (which incorporates Sasol’s fuel production businesses), Travel and Leisure, Listed Property and Banks.

Our portfolios were helped by our overweights in Tobacco and Personal Goods, but hindered by our Health Care and Food Producers underweights. Our Chemicals overweight (Sasol) fell dramatically as the demand for fuel declined amid travel restrictions and slower economic activity, but we benefited slightly from our Life Insurance and General Retail underweights.

On the style front, our strong value exposure was a detractor from our equity performance, as was our underweight to low volatility stocks and quality, and our high beta overweight.

In bonds, our overweight to the long end of both the real and nominal yield curves led our fixed income funds to struggle through much of 2020, as the yield curve underwent more dramatic moves in a single quarter than most fixed income managers have seen in their lifetimes. However, our fixed income funds saw a strong recovery in 2021 and have continued to generate excellent returns through 2022. The same was largely true for our multi-asset fund performance, given our equity and bond positioning.

Risk management and the Covid crisis at M&G Investments

Our risk management process exists to manage the third – controllable – element of portfolio risk noted above: active asset exposure. All our portfolios are run with risk limits in mind: we measure these using tracking error for equity and multi-asset portfolios, and duration limits (absolute or relative) for our fixed income portfolios. Duration takes into account a bond’s (or bond portfolio’s) overall maturity, yield, coupon and call features to determine its interest rate risk, or how sensitive its value is to interest rate changes. Generally, longer-dated bonds have higher duration, and therefore present higher risk to investment portfolios.

These risk limits are either agreed with segregated clients as part of the investment management agreement, or for our unit trusts, they are set internally with reference to the portfolio’s expected risk characteristics, required returns and investment strategy. We closely monitor all our portfolios to ensure they stay within these specified limits.

During the height of the Covid crisis, we increased the frequency of risk monitoring and reporting to the investment team. For the multi-asset funds, we performed scenario analysis to understand how our risk was split between stock selection and asset allocation risk. We did this by constructing multiple “paper portfolios” which each isolated one aspect of the portfolio’s construction at a time, splitting out the asset allocation decision for each asset class, from the security selection within an asset class.

We noted sharp increases in tracking error during March 2020, but were able to see that about two- thirds of this came from increased market volatility, with the remainder from earlier changes to our active positioning since the end of December 2019. This gave us confidence that the tracking error increases would only be transitory, and therefore when we experienced breaches of the risk limits by a handful of portfolios, we were able to wait out the short period it took for the active risk to come back down to acceptable levels.

In one breach, for example, strong divergences in equity performance across the globe meant that, briefly, our 14% holding of the M&G Global Equity Fund in the Dividend Maximiser Fund (where the fund gets its offshore equity exposure) was contributing nearly 40% of the portfolio’s active risk. This situation normalised of its own accord over the following months

Consequently, we did not have to de-risk any portfolios by selling certain assets to conform to risk limits. This was a very positive development because, during a crisis, tremendous opportunities arise for active managers, and asking them to move to cash or sell out of underperforming (and often very cheap) positions is likely to lock in losses and destroy value. Instead, our equity team was able to take advantage of excellent opportunities at the bottom of the market; similarly, divergences in asset class valuations meant that the multi-asset team was, for example, able to snap up inflation-linked bonds at some of the cheapest valuations ever seen.

An investment risk process is – by its nature – usually countercyclical, calling for decreases in risk in portfolios at exactly the wrong time. Awareness of this tension, combined with well-set risk limits, timely data, understanding of risk sources, patience, and established risk reporting, not to mention our prudent portfolio construction processes, carried us through the Covid crisis and into the recovery. There, the moderately bullish positioning with which we’d entered 2020 was able to generate alpha over subsequent periods.

For more information:

1. https://www.mandg.co.za/insights/articlesreleases/market-observations-q4-2019/

2. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/01/20/weo-update-january2020

For a cogent economic history of the Covid crisis, Adam Tooze’s book “Shutdown” cannot be recommended highly enough. Tooze is one of the premier economic historians of our time and has managed to achieve sufficient distance from his subject to present an ordered account of a period that, for most market participants, was a blur of activity and rapid news flow.

Share

Did you enjoy this article?

South Africa

South Africa Namibia

Namibia

Get the Newsletter

Get the Newsletter