When traditional risk measures deceive

These days, investors are arguably as concerned, if not more so, about what risk-adjusted returns they are earning as they are about the level of absolute returns achieved. This is a good thing. Thinking in risk-adjusted terms allows investors to gain a better understanding of financial products and to find solutions more suited to their risk tolerance. However, this only works if the risk measure that you are relying on is telling you something sensible about how much risk you are actually taking.

As an industry we have come to gravitate around volatility, or some variation thereof, as our risk measure of choice. Indeed, charts that show managers’ returns relative to the volatility of their portfolios are commonly referred to as “risk-return charts”. Furthermore, the most popular measures of risk-adjusted returns use volatility in the denominator, implying that volatility and risk are very narrowly related, if not equivalent. For the most part this rule of thumb works well. But in instances where it fails, it can lead to bad investment decision-making.

Does return volatility = risk?

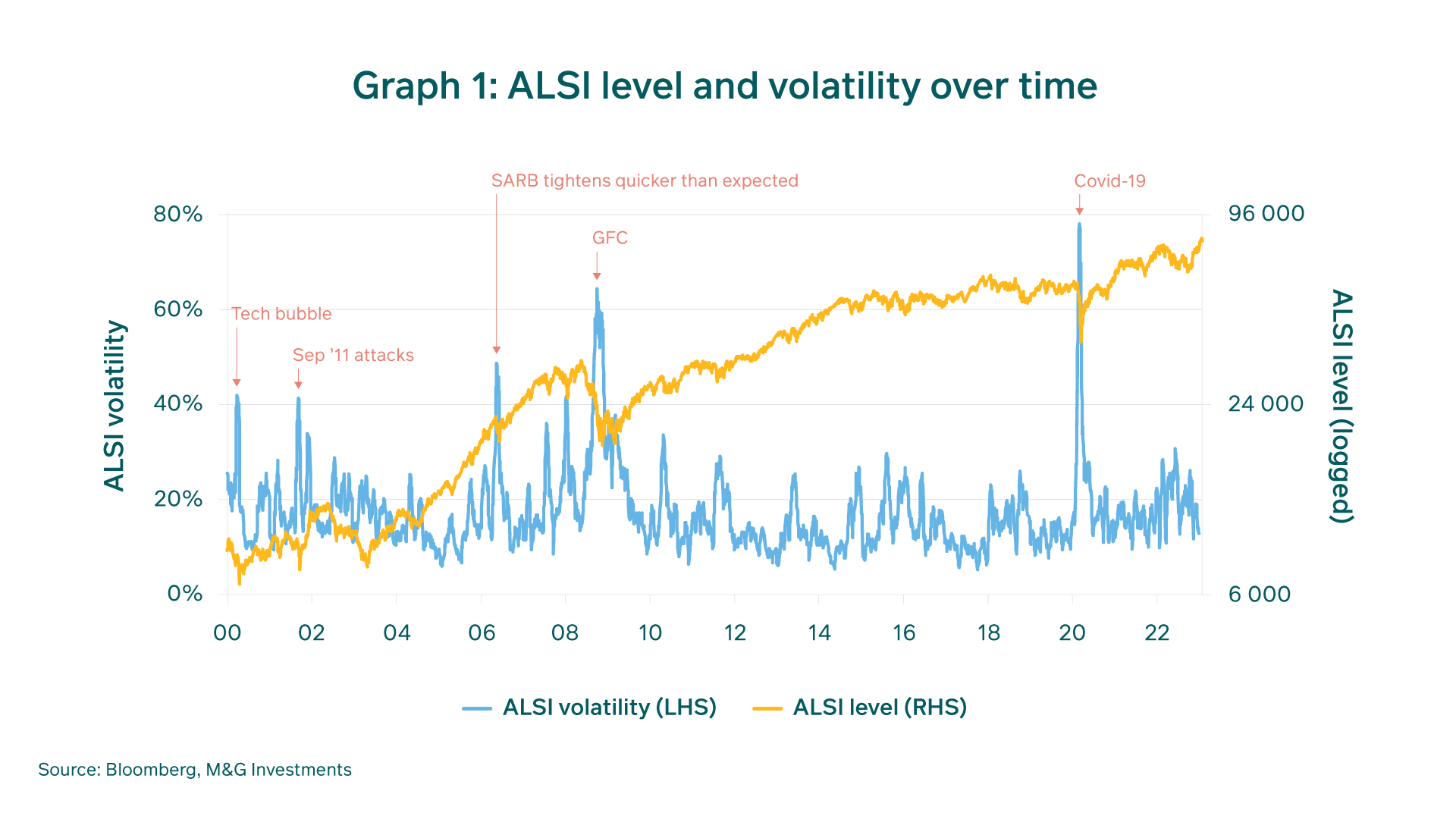

We would argue that volatility of returns should be a good proxy for risk, or investment uncertainty, within markets that are deep, liquid, and well-functioning. Take the South African equity market as an example. The volatility of the index, as a whole, has historically tended to spike during periods which most of us would consider to have been of heightened economic uncertainty (see Graph 1). This rule of thumb also appears to work well on a bottom-up basis. If you were to compare the volatility of individual shares across a universe, you would tend to find companies in Consumer Staples, mature businesses and less leveraged names (operationally and/or financially), at the lower end of the spectrum. Resource shares, and companies that are highly leveraged, should dominate the more volatile end. Arguably, the market does a fairly good job at distinguishing between companies with highly certain and more uncertain financial prospects.

This stands to reason. If we think about what the share price of a company represents, it is by definition the market’s expectation of its discounted future cashflows. If that share price is moving around a lot, this tells you that the market is uncertain about what the future holds for that company.

Beware the exceptions

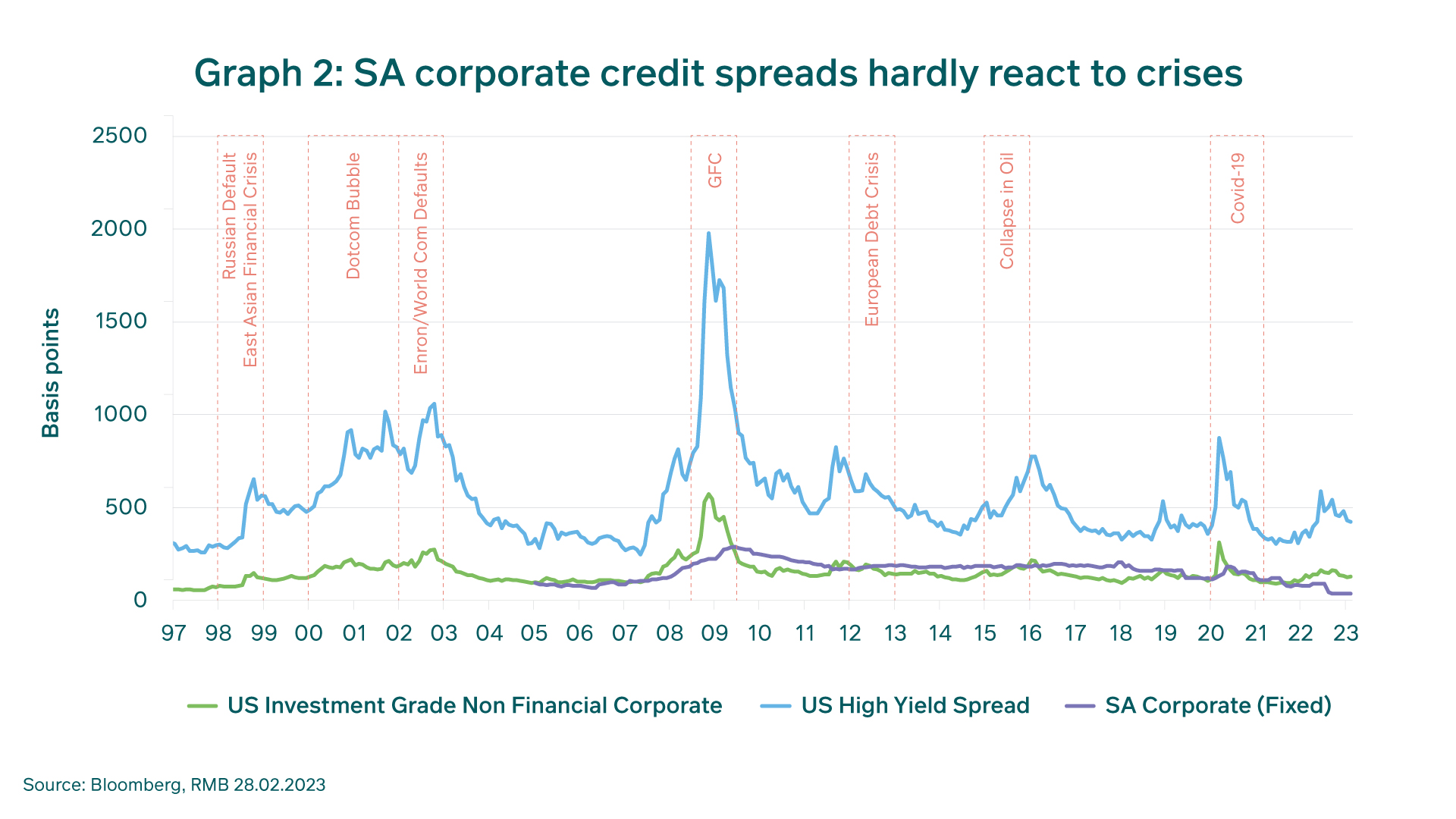

This rule of thumb (volatility = risk), however, tends to break down in markets where market-depth and liquidity are less prevalent. An example of such a market is the market for South African listed corporate debt. Our credit market is much less reactive in periods of heightened uncertainty, as shown in Graph 2. For example, credit spreads, which indicate the risk of default of a corporate borrower compared to government risk, hardly budged during the COVID pandemic. The volatility of a typical SA credit portfolio would not, at the time, have signaled the prevailing market stress.

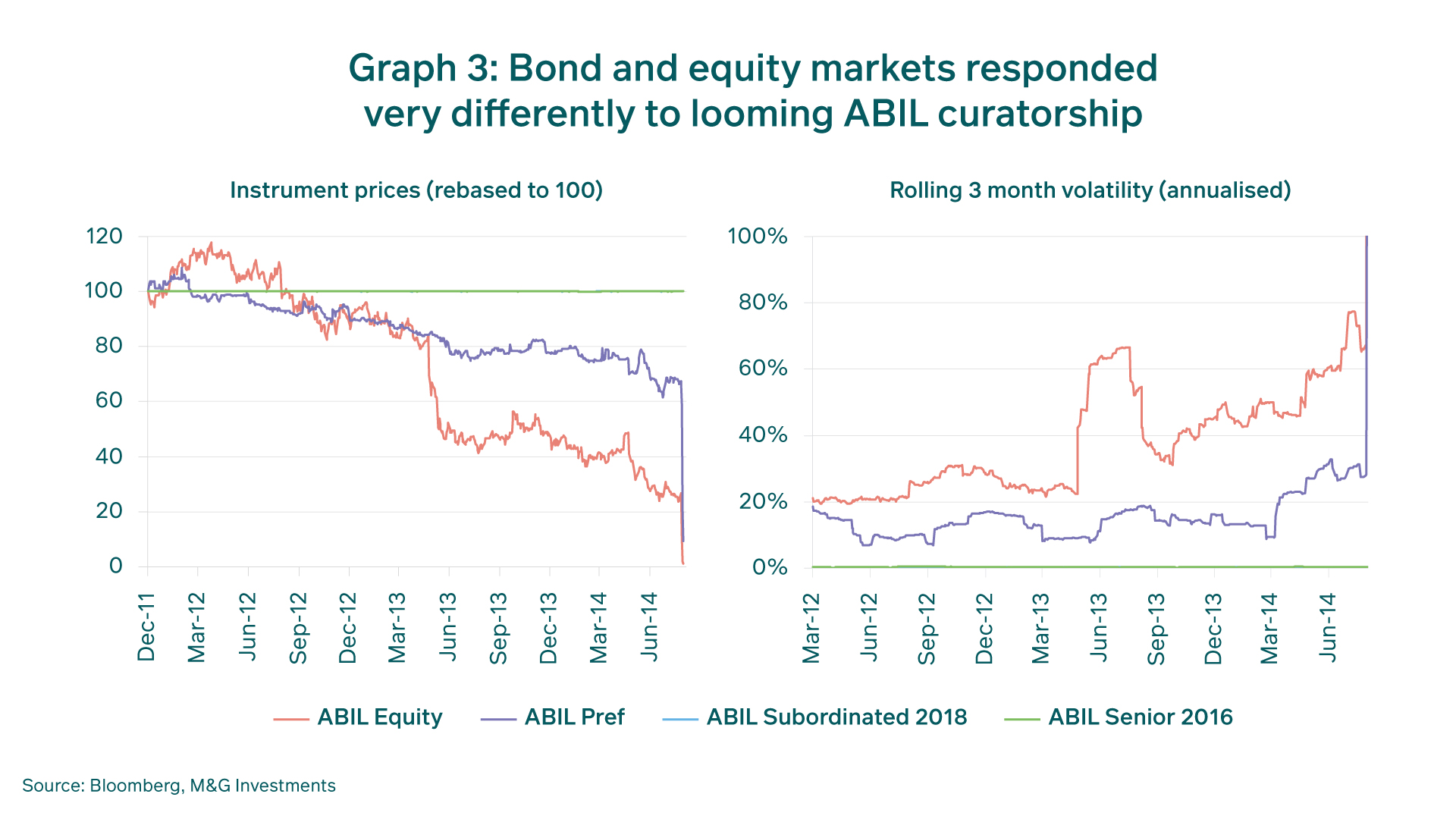

Our rule of thumb works no better for SA credit on a bottom-up basis. Had you, for example, been an investor in African Bank’s debt instruments just before the bank went into curatorship in August of 2014, you would not have been aware that anything was amiss by looking at how your portfolio was behaving. As Graph 3 illustrates, your bonds would still have been trading at par, with no volatility. By this point, ABIL equity and preference share investors would have lost substantial portions of their initial investments and would have seen the volatility of these instruments increase. Clearly, the volatility of your debt investments would have told you nothing about the amount of risk that you were exposed to at the time; more specifically, that you were about to take a haircut a result of the looming curatorship event.

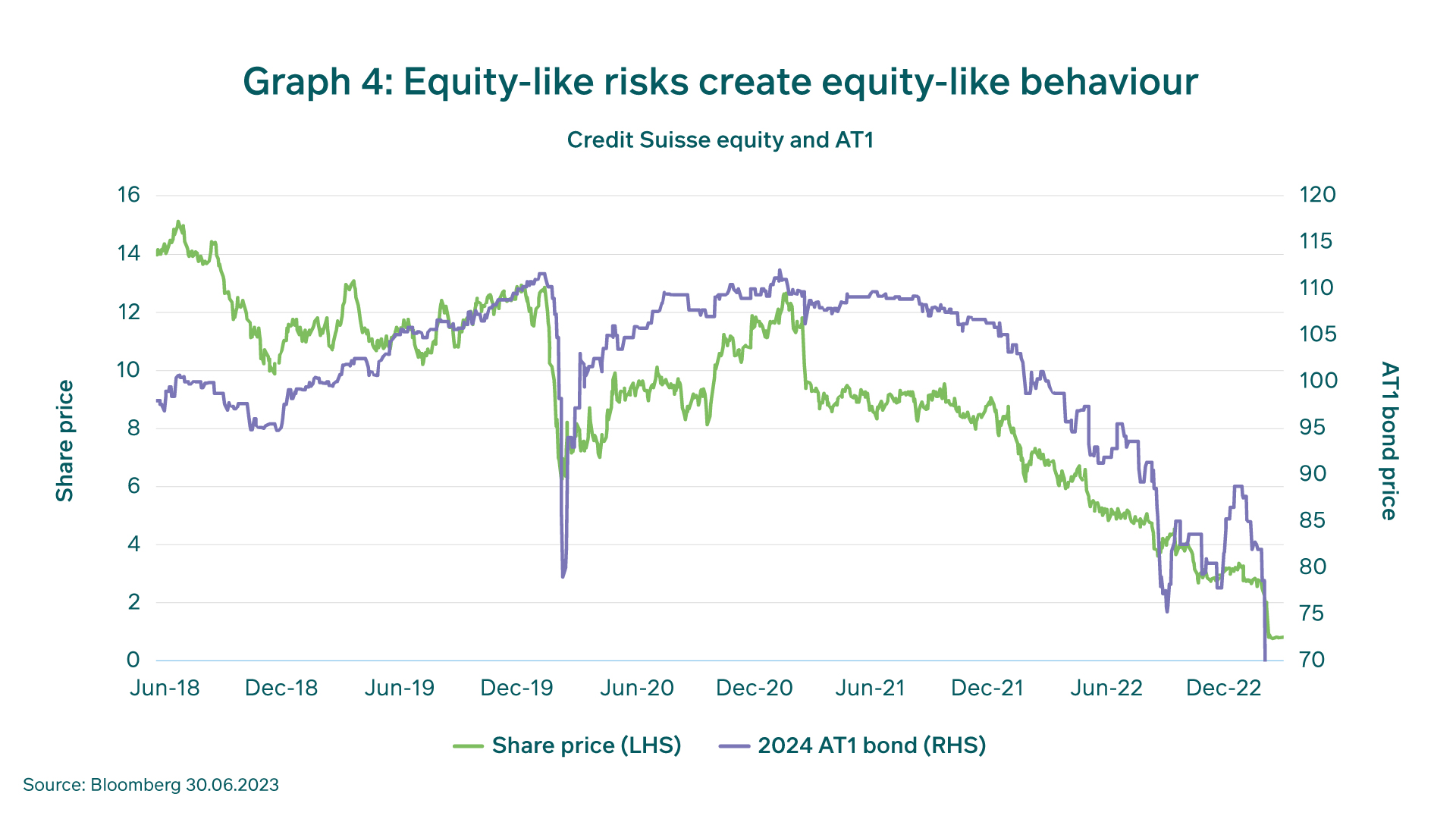

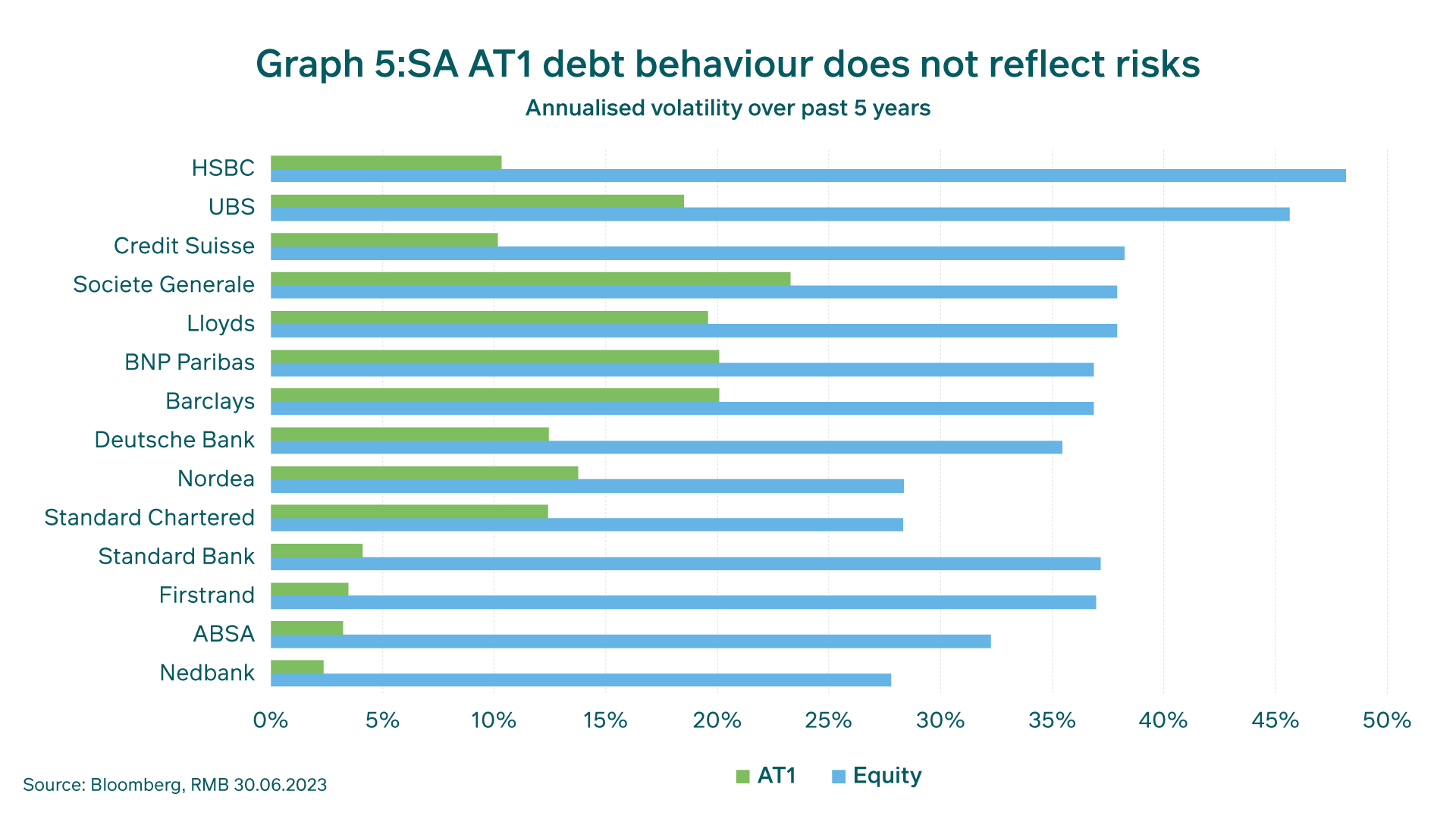

Additional Tier 1 (or AT1) bonds provide another interesting example of a divergence between volatility and risk. These are the most junior debt instruments that banks issue. AT1 bonds have some equity-like features embedded in them, such as the regulator’s ability to write them off completely, should the bank end up in so much trouble that its viability becomes questionable. These equity-like features were on full display in March of this year, when investors holding US$17bn of Credit Suisse AT1 bonds were completely wiped out when the bank ran into difficulties and was acquired by UBS. Even though the regulator ruled that the bank’s AT1 bonds were to be written off completely, Credit Suisse’s shareholders still managed to walk away with $3.2bn. This experience demonstrates that AT1 investors should expect to suffer equity-like (or worse) losses from time to time when things go wrong. It would therefore stand to reason that such equity-like risks embedded into AT1 bonds should translate into equity-like price behaviour as well as equity-like volatility. This is indeed the case in the European market, but not so in SA, as can be seen from Graphs 4 and 5. In SA, AT1 bond volatility is in fact money market-like and completely inconsistent with the investment risk inherent in this instrument class.

Illiquidity distorts the risk picture

So why exactly is it that market volatility does such a good job at pointing out the risks in equity markets, but is no good at identifying credit-related risks? The short answer is that credit, in South Africa, hardly trades[1]. Most investors consider it to be a buy-and-hold investment, and appear to treat it as such. Because there is much less market activity that happens in the instrument class, there is no or little price discovery that takes place. And without arms-length transactions taking place between unrelated parties, there isn’t the mechanism for the market to embed the uncertainty into the instrument price, as would be the case for equities.

The SA credit market is not the only asset class which sees its volatility behaving inconsistently with its investment risk. Alternative assets (e.g., private equity) and non-traditional assets (such as institutional investments in farmland, art, etc.) are similar in this regard. Proponents of these types of investments will often tout their low volatility, and lack of correlation with equities, as useful investment features. However, we would argue that these features are likely an illusion, brought about by a lack of liquidity (which, all things being equal, is a drawback).

Corporate credit needs careful analysis

All of this does not mean that SA credit has no merit for investment purposes. Indeed, we have significant exposure to credit across a range of client mandates. However, the only justifiable reason for holding a credit position should be that you expect to earn a greater additional return, in the form of a credit spread, than the expected credit losses (in the form of defaults), from such positions over time. The fact that credit exposure comes with good risk-return optics for your portfolio should play no part in the decision.

Investors should try to recognize situations where traditional risk measures are of little use. If a large portion of the assets that you, or your fund manager, holds, does not regularly change hands in the secondary market, even the most sophisticated risk model available is unlikely to tell you anything useful. When it comes to SA credit, try to get a sense of the creditworthiness of the issuers that you are exposed to, as well as how senior your investments rank within the various capital structures. Beware of investment opportunities that give the impression of returns significantly in excess of the risk-free rate without accompanying additional volatility. Such situations do not arise naturally withing a capitalist system. Corporate treasurers don’t tend to give away money for free. If an issuer is paying you 300 basis points above JIBAR for lending it money, you are most certainly taking some investment risk, even if traditional risk metrics tell you otherwise.

[1] “An alternative anchor for credit spreads”, Avior Capital Markets, Q4 2017. The researchers show that SA credit turns over in the secondary market at a rate of between 2% and 10% per annum. This is between 20 and 50 times lower than SA fixed-rate government debt.

Share

Did you enjoy this article?

South Africa

South Africa Namibia

Namibia

Get the Newsletter

Get the Newsletter